So important to the European art world and yet relatively unknown in Belgium: Flemish artist Jef Verheyen (1932-1984) returns to Antwerp. Forty years after his death, the KMSKA presents the first museum solo exhibition of this illustrious modern master in his hometown. A first.

Jef Verheyen. Window on Infinity closely follows the evolution of this modern master. We see how he moves from ceramic experiments to painting, constantly refining the medium. In light and dark, in form and color. New archive research reveals how Verheyen bridges the gap between tradition and innovation, between present and future. In search of the essence, in the infinite. Everything to make us look differently and see more. Let that be the exact motto of the KMSKA.

Movement, color, and light

When you stand before a work by Verheyen, it seems as if particles, like clouds, softly drift past. All colors between black and white appear in elusive arcs of light and sunbows, rainbows and moonbows, sometimes in diamond shapes, sometimes in a composite composition. In bright colors, Verheyen paints homages to Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), kindred seekers of light.

“In both ceramics and my paintings, I tried to achieve a kind of ‘essence’ beyond the formal.”

Contemporary resonance

The curators have also invited contemporary artists to cast light on Verheyen’s role as a pioneer of a different way of looking at art. Installations by Ann Veronica Janssens, Kimsooja, Carla Arocha & Stéphane Schraenen and Pieter Vermeersch will intensify visitors’ spatial and visual experience of the exhibition.

Jef Verheyen: Window on Infinity is a collaborative project between two Antwerp partner museums, the KMSKA and M HKA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Antwerp). This exhibition is the result of extensive research performed by M HKA in cooperation with the Jef Verheyen Archive.

The last modernist

As with many major crises, World War II represents a turning point for the arts. Verheyen and other artists of his generation asked themselves: what is the essence of art? They thought conceptually about art history, fostering a desire to push art further without necessarily rejecting the past. It was about breaking down the partitions between disciplines. Many of his contemporaries left painting, while Verheyen steadfastly stuck to it.

Verheyen felt akin to the pursuit of the conceptual, but at the same time, he nurtured a great love for craft. Yet, Verheyen was a child of his time. The idea of what painting could be had fundamentally changed. Through monochromy, Verheyen evolved towards an artless art. By painting in washed layers without brushstrokes, he deliberately directed the viewer’s gaze beyond his paint to the light, to infinity. It was necessary to look beyond the flat surface, to actually see through it—into the void or space. This was partly literal; the space race between the United States and Russia was raging in full force at the time, reflecting a broader societal push towards new frontiers.

“I paint to see.”

Initially, Verheyen incorporated his interests into ceramics. Beginning in 1957, his early paintings started to prominently feature circles, loops, half-moon arcs, and spheres. The movement of Abstract Expressionism, particularly evident in the works of young American artists, also served as a significant source of inspiration for him. Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), for instance, adopted the Eastern tradition of engaging with the canvas directly on the ground, akin to making calligraphic marks, which influenced Verheyen’s approach.

Monochromy and identity

In 1957, a significant turning point occurred for the 25-year-old Verheyen when he moved to the modern metropolis of Milan. There, he met Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), the Argentinian-Italian painter, sculptor, and theoretician. Verheyen found a soul mate in Fontana, particularly in his Concetto Spaziale series, which explored the spatial dimensions of art.

As early as 1946, Fontana had advocated for a novel approach to time and space in his Manifesto Blanco. Despite the age difference, Verheyen and Fontana found common ground, as evidenced by the letters they exchanged. In Milan, Verheyen also established connections with artists Roberto Crippa (1921-1972) and Piero Manzoni (1933-1963), further enriching his artistic journey.

The impact of Manzoni’s achrome art on Verheyen’s work was profound, prompting a shift from labyrinthine, cosmic paintings to pure monochromes, painted in a single color, representing a new essence. The black monochrome painting Veil of Mystery (1958-1959) stands as a pivotal work in this development.

“Black has always seemed more matter than white to me. Black is thus matter itself. White is matter separate from matter. Matter-free. Complete space. Black is a dead colour.”

To his Milanese friends, Verheyen was hailed as a ‘true Flemish artist,’ highlighting the international appeal of the Flemish art tradition—an eye-opener for him. Verheyen had already embraced the glazing technique pioneered by Jan van Eyck (1390-1441). With the slogan Ligt de universaliteit in de traditie?‘ (‘Does universality lie in tradition?’), Verheyen and Englebert Van Anderlecht (1918-1961) founded the New Flemish School in 1960, aiming to establish Antwerp as a hotspot for the international avant-garde.

On another note, he began to title his paintings with names like Flemish place or ‘Espace Flamand,’ through which Verheyen explored his identity as a Flemish painter. These titles reflect more an idea of Flanders—as he perceived it in the landscapes of Constant Permeke (1886-1952)—rather than specific observations of a place.

Movement, colour, light

Monochrome painters believe that pigments by themselves can suggest movement. Pollock must sway his brush to obtain movement. Verheyen, Yves Klein (1928-1962) and co take a different approach to ‘movement’.

Standing in front of a work by Verheyen, it seems as if particles, like clouds, seem to slide gently by. It is a kind of static movement, generated by paint and technique. Verheyen sees an echo of this in the colour fields of Mark Rothko (1903-1970).

From the early 1960s, Verheyen integrates more colour, and light. If you let a prism refract the light you see a spectrum of colours. The artist believes you don’t necessarily have to paint that whole spectrum to create the illusion that those missing colours are there after all. Panchromia, it’s called. All the colours between black and white appear in elusive arcs of light and sun, rain and moon arcs, sometimes in diamond shapes, sometimes in a composite composition. In bright colours, Verheyen paints homages to Claude Monet (1840-1926) and Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), kindred light seekers. Verheyen’s light is again more of an idea, a sense, than the light he sees from his studio window, which makes him an abstract artist. He refers to James Ensor (1860-1940), who at a late stage of his life made drawings and paintings in very light pastel tones.

Verheyen feels akin to the pursuit of the conceptual, but at the same time nurtures a great love of craft. Yet Verheyen is a child of his time. The idea of what painting can be has fundamentally changed. Verheyen grows via monochromy towards an artless art, By painting without brushstrokes in washed layers, he deliberately sends the viewer’s gaze beyond his paint to the light, to infinity. You have to look beyond the flat surface, actually look through it. Into the void, or space. Partly literally, the space race between the United States and Russia is raging in full force at the time.

“The impressionists see the light first, then they feel; I feel first then I see. I believe Monet personified himself with pure colour.”

ZERO movement & cooperation

With his exploration of the phenomenon of ‘light’, Jef Verheyen connects with the ZERO movement in Italy, Germany, Switzerland, France and the Netherlands. On his painting front, as they get to work with lamps, reflectors and mirrors.

Despite the difference in artistic practice, Verheyen finds companions in the movement to collaborate multimedia with. He reveals himself as a curator and engages his international network for total concepts in which craft, science, art and architecture merge. Jef Verheyen puts post-war Antwerp on the map alongside Milan, Paris, Düsseldorf and Amsterdam.

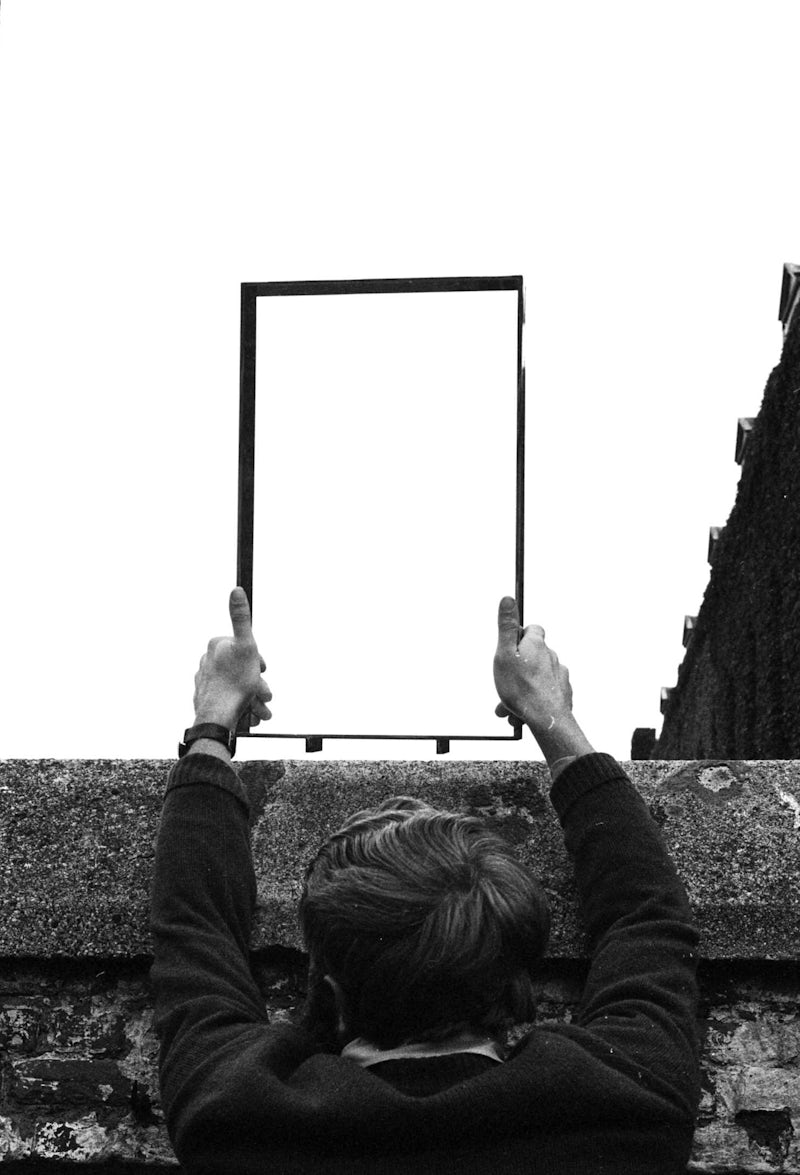

Fontana, Van Anderlecht and Hermann Goepfert (1926-1982) are the dream partners who put their shoulders under the hybrid art forms. Within the group of ZERO artists, it is mainly with Günther Uecker (°1930) that Verheyen builds a close friendship. Brotherly, they organised the open-air exhibition Flemish Landscapes in the countryside in Mullem in 1967. The duo places a large window frame in the landscape to direct the gaze to the sky, as a tangible window to the infinite. It is the complete dematerialisation of art, and one of the most conceptual interventions of Verheyen’s career. It does not end with this performance. The artist also creates small versions with titles like Le Vide and Le Plein, and also integrates the ‘bounding of nothingness’ into his painting.

“A window properly placed today can hold more mystery than a thousand candles and two Christ statues.”

ZERO International Antwerp

In 1979, Jef Verheyen curated the ZERO International Antwerp exhibition at KMSKA. In the following years, the museum bought several works by members of the ZERO movement, often from the artists themselves, including Verheyen. This international ensemble is the last ensemble to be given an integral place in the museum’s collection and includes names such as Lucio Fontana and Günther Uecker, Verheyen’s friends.

Cathedrals of light and geometry

After experimenting with archetypes, colour and light, Verheyen refocuses his gaze on shapes in those fertile 1960s. He introduces tondos, round paintings, which in Italian art history hang higher than classical paintings. At the same time, the circle is an infinite form, which also has symbolic value in the East. With a triptych like Cathedrals of Light, Verheyen unites his research into colour, light and (the Gothic) form.

‘Decreasing light is increasing darkness’, and vice versa. For Verheyen, day and night are like the breathing of the world, which he wants to represent. Natural phenomena and the basic elements earth, air, fire and light become his alpha and omega. From those basic elements, he even pours out an experimental film, an early artist film, Essential, which has a place in the expo.

Meanwhile, Verheyen continues to search for the light that is different everywhere. It leads him away from the Flemish landscape to Brazil, Mexico, Spain, Italy. Finally, in 1974, he moves from Antwerp to Provence.

In mathematics and Greek philosophy, Verheyen finds a basis for harmony and the ideal space. Geometric basic shapes or perspective lines are the foundations of Verheyen’s later paintings. Between 1980 and 1984, he transforms, among other things, diamond-shaped mirrors into trompe l’oeils. The shapes seem to float in an unlimited space, like a window on the infinite. The circle is complete.

‘Diminishing light is increasing darkness’, and vice versa. For Verheyen, day and night are like the breathing of the world, which he wants to represent. Natural phenomena and the basic elements earth, air, fire and light become his alpha and omega. From those basic elements, he even pours out an experimental film, an early artist film, Essential, which has a place in the expo.

Meanwhile, Verheyen continues to search for the light that is different everywhere. It leads him away from the Flemish landscape to Brazil, Mexico, Spain, Italy. Finally, in 1974, he moves from Antwerp to Provence.

In mathematics and Greek philosophy, Verheyen finds a basis for harmony and the ideal space. Geometric basic shapes or perspective lines are the foundations of Verheyen’s later paintings. Between 1980 and 1984, he transforms, among other things, diamond-shaped mirrors into trompe l’oeils. The shapes seem to float in an unlimited space, like a window on the infinite. The circle is complete.

Contemporary masters

Verheyen explored a different way of experiencing art, which seems obvious today. But is it? How do artists today deal with the infinite, light or colour? Ann Veronica Janssens, Kimsooja, Pieter Vermeersch and the tandem Carla Arocha-Stéphane Schraenen take up the challenge with dynamic light installations or mirror paintings Just like Verheyen, they break through the boundaries of painting to stimulate the visitor’s visual amazement.

Bridge builder

The Jef Verheyen Archive found its home at the Centrum Kunstarchieven Vlaanderen (CKV) in the M HKA. From the letters, diaries, essays, manifestos, Verheyen clearly emerges as a bridge builder. With great love for the craft of, for instance, Jan van Eyck, whose two works the KMSKA owns. At the same time, the painter finds the idea more important than the execution. Jef Verheyen. Window on the Infinite shows the usually underexposed conceptual aspects of Verheyen’s art, thus acting as a linking figure between the KMSKA and the M HKA, between tradition and innovation.

Online platform

Visit jefverheyen.ensembles.org to find a wealth of information about Jef Verheyen, the archive and the exhibition in KMSKA.

Colophon

Jef Verheyen. Window on Infinity is a collaboration of two Antwerp partner museums, KMSKA and M HKA (Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen). This exhibition is the result of extensive research by M HKA in collaboration with the Jef Verheyen Archive.

Curators: Adriaan Gonnissen (KMSKA) & Annelien De Troij (M HKA)

Image: Jef Verheyen en Lucio Fontana, Rêve de Möbius (1962), Collectie Jef Verheyen Archief